Listening is often lumped together with speaking instead of being considered by educators as an entity in itself. However, listening is an important part of language development and should not be overlooked by teachers as they plan and implement classroom instruction. As with reading, listening requires an active process in which students use their previous knowledge and experiences of the topic and the language to construct meaning from what they’re hearing. David Nunan (1990) refers to the listener as a “meaning builder” (Gibbons, 2015, p.184). Understanding the spoken words requires more information than just listening to the sounds and words that are said.

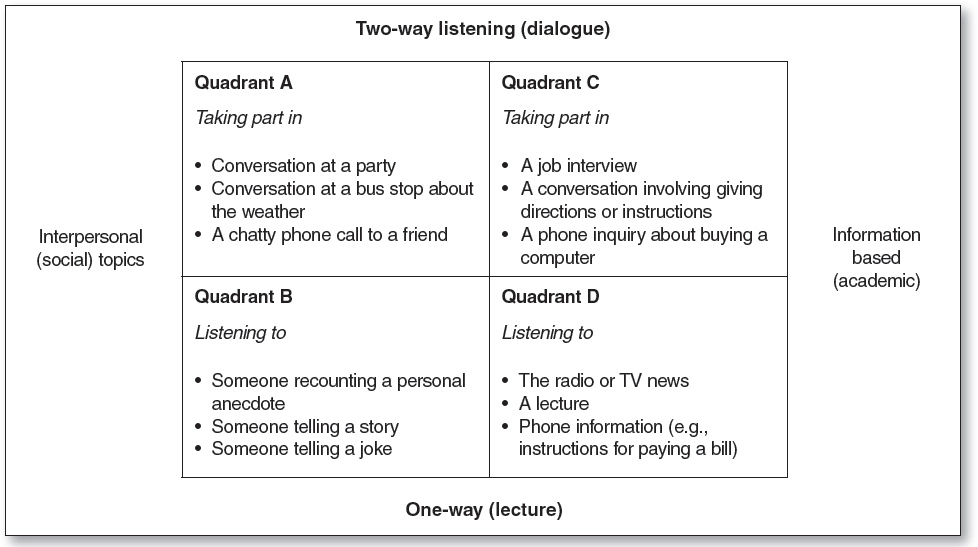

“Nunan (1990) has suggested that listening occurs in four types of contexts, which he set out as a matrix” (p.186). Listening can be one-way such as students listening to the teacher presenting a direct teach lesson or listening to news on the radio. It can also be two-way, in which two people take turns being the listener and the speaker. Two-way listening allows the opportunity for the listener to ask the speaker to slow down, repeat a portion of what he said or to ask clarifying questions. Both types of listening can take place in two different contexts—everyday conversation such as discussing the weather or a favorite video game and informative conversations like giving directions or listening to a lecture. For EL learners, two-way listening in the context of interpersonal topics is the easiest and one-way listening in an informational context is the most difficult.

Educators can help students learn to listen actively by engaging them in activities for the sole purpose of introducing how to listen, then providing specific activities for both types of listening: one-way and two-way listening. For example, have students be completely silent, close their eyes and listen. After a few minutes, give them the opportunity to share what they heard and discuss what active listening feels like. In the case of two-way listening, EL learners often don’t know how to ask the speaker to clarify what was said, to repeat themselves, or to provide more information. Teachers can assist EL learners by modeling and practicing phrases such as, “I’m sorry, I don’t understand. Could you repeat that?” and “Excuse me, I’d like to ask something” (p. 189). Creating an anchor chart with students and displaying it for reference is beneficial so using the phrases in class becomes a natural part of student learning. Teachers should ensure that all students know it is okay to ask questions or to ask for clarification.

Barrier games are effective for increasing two-way listening skills. Two students have a problem to solve, but they each have different information—photographs, illustrations, maps, or text to read. Instead of looking at each other’s materials, they solve the problem by explaining to each other what they see or read on their resource. This requires both students to speak with clarity and actively listen to each other for understanding. For more information on barrier games, see Chapters 3 and 5 in the book Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning (Gibbons, 2015).

To practice one-way listening, teachers can give students directions asking them to write specific words or drawing on a certain area of their papers such as “If you are a boy, write it (name) on the left. If you are a girl, write it on the right”. (p.194) Another activity Gibbons calls “Hands Up” involves giving students a list of questions before reading a text aloud to them and asking them to raise their hands when they hear information from the text that answers one of the questions. Providing students with a note-taking page that already has an outline or bullet points to listen for is a third way to practice one-way listening. The teacher tells students the topic they will learn about, gives them the outline, and asks them to listen for the specific line items listed on the outline. For example, if the teacher reads a books about animals, the outline might contain name of animal, habitat, food, and defense mechanism.

Gibbons also includes information for educators about teaching EL learners how to focus on the sounds of the English language. “One aspect of spoken English that some EL students may find hard to master is its stress system”. English is spoken with different pronunciations around the globe, so even EL students who have learned some English in their native country may not understand the English spoken in the classroom. Providing activities such as chants and raps will give students the opportunity to “focus on the rhythms, stress, and intonation patterns of English”. Other activities to help EL learners with how English sounds that Gibbons explained in Chapter 7 are: Minimal Pair Exercises, Say It Again, and Shadow Reading.

In conclusion, educators must regard teaching listening as a vital part of their instruction because learning to be an active listener is an essential aspect of language development. One way teachers can show students they value listening is to be active listeners themselves. Modeling listening strategies by paying attention to what students say and asking them for clarification when comprehension breaks down expresses to students the importance of listening.

References:

Gibbons, Pauline. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning Teaching English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann

Nunan, David. Listening Matrix. [Table]. Retrieved from https://sk.sagepub.com/books/ell-shadowing-as-a-catalyst-for-change/i193.xml