In their

book Teaching Language and Literacy: Preschool Through the Elementary Grades (5th

ed.), Christie, Enz, Vukelich, & Roskos (2014) promote teaching writing to

elementary school students with a workshop structure. Teachers should allow

45-60 minutes per day for the writing workshop block and classrooms should be

arranged to provide spaces for students to work on their writing independently,

with partners or in small groups. This structure consists of an initial

mini-lesson, then time for students to write while the teacher conducts individual

student conferences, and finally a sharing time in which students read aloud a

portion of one of their writing pieces for the whole class or a small group of

peers.

Mini-lessons: The initial mini-lesson, also

referred to as a focus lesson, is short and concise, lasting approximately 10

minutes. At the beginning of the year, these lessons teach students the structure

of writing workshop and include topics such as peer conferencing,

teacher-student conferencing, and classroom procedures for editing, proofreading,

and publishing. Students are taught expectations for each of these situations

including the type of support they will be offered by the teacher and their

peers. After students understand the structure of the writing workshop and

routines are in place, focus lessons should provide explicit instruction in

three areas: qualities of writing, steps of the writing process and conventions

of language.

- Qualities

of writing—Instruction should include setting a purpose to write, the

characteristics of different genres, and how to analyze mentor texts for craft

moves that students can mimic in their own writing

- Writing

Process—Students should be taught that the writing process is ongoing.

Although, there are specific steps to writing (prewrite, draft, revise, edit,

publish), authors move back and forth within the writing process steps

frequently as they reflect on what they’ve written and revise to improve it.

- Conventions

of language—Teachers should provide instruction about “punctuation, grammar,

usage, handwriting, capitalization, and spelling”. (p.323) State and district

standards should be used as reference to identify which skills should be

included in these lessons.

In addition

to using state and district standards as a guide, the students’ writing itself should

drive classroom instruction. Teachers should use data they collect from ongoing

assessments of students’ writing during the year to determine what type of

focus lessons are needed and adjust instruction accordingly.

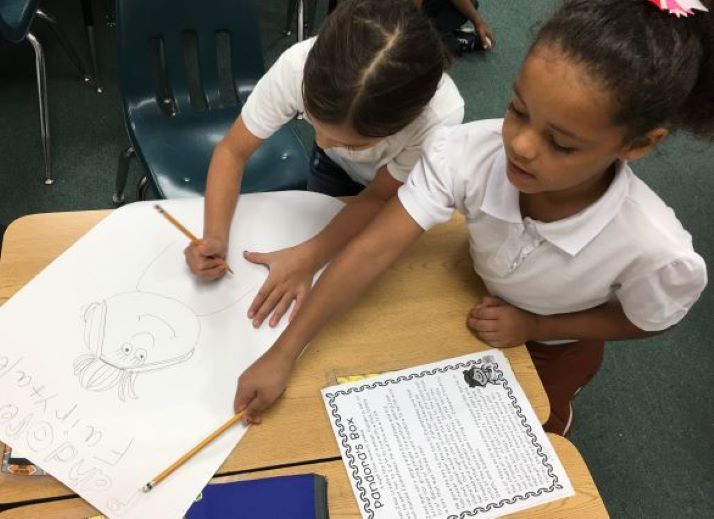

Writing Time and Student Conferences: The bulk of the time in a writing

workshop is allotted for students to write. During this time, each student

works on what he needs so students will be doing a variety of activities within

the writing process steps. For example, a few students may be working

independently to generate topics for a new writing piece, some might be

studying mentor texts to analyze the author’s craft and apply it to their

writing, and others may be collaborating together on revising their pieces. While

students are writing, the teacher conducts conferences with individual students

to provide differentiated instruction. Christie, et al. suggest the following

outline for teacher-student conferences:

- Writer’s

Intent: Initially, the teacher asks the student what he is working on to

research his intent or direction in order to determine the writer’s goal and

plan instruction during the conference.

- Writer’s

Need: The next step involves asking the student a few guiding questions to

direct the conversation in a way that will help the student improve as a

writer. The teacher needs to determine one or two aspects of the student’s

writing ability to focus her instruction on for this specific conference.

- Teach

the Writer: During the teaching step, the teacher provides instruction to the

student by showing him a mentor text that will help him improve in the specific

area identified, referring him back to previous writings, letting the writer

know something is confusing or missing, or perhaps asking questions to assist

the writer in self-reflection. This teaching piece is very brief and should not

be presented lecture-style, but delivered through conversation.

- Writer’s

Plan: In this last step, the teacher asks the student to articulate a plan, or

what his next steps will be as a writer. The teacher may need to provide a

sentence starter such as, “Now you’re going to…..” and wait for the student to

respond.

Tracking

teacher-student conferences by taking a few notes about the writer’s need, what

instruction was provided and the writer’s next steps is beneficial. The teacher

can use these notes to ensure she meets with all students regularly and to

determine if the students are showing growth by following through with their

stated plans as well as determining what focus lessons are needed by the

majority of the class.

Sharing: The last 10-15 minutes of a writing

workshop period consists of a group share time. Here are the different types of

share sessions Christie, et al. presented in Chapter 10:

- Share

meeting—students share drafts while the teacher and students ask questions,

some students may share specific strategies they’ve recently learned or tried

in their writing

- Writer’s

circle—the class is divided into small groups and sharing is conducted within

each small group at the same time which allows for more students to share in a

small amount of time

- Quiet

share—students bring writing utensils and paper to the share time so they can

write down questions or comments as the writers share their pieces (papers are

given to the writer to review later)

- Focused

share—the teacher asks students to read a specific component of their writing

piece such a their lead, their closing, or an example of descriptive language

- Process

share—students are asked to bring an example of a revision they made and

explain their thinking about why they made the change

- Celebration

share—students share completed writing pieces as a celebration of their hard

work

Some

examples of what students might share are graphic organizers or lists in which

they’ve generated writing topics and ideas, drafts they’ve started to show

specific components of their writing such as sensory language or to ask for

revision suggestions, particular phrases, sentences or paragraphs in which they’ve

imitated a mentor author, or possibly a completed writing piece that is ready

for publishing.

Teaching Mechanical Skills

In Chapter 11, Christie, Enz, Vukelich, &

Roskos (2014) suggest that even though students receive instruction for mechanical

skills of writing such as spelling, grammar, capitalization, punctuation and

handwriting through using editing checklists and teacher-student conferencing

during writing workshop, these activities may not be enough. Explicit

instruction is needed to strengthen mechanical skills for students to be

successful writers.

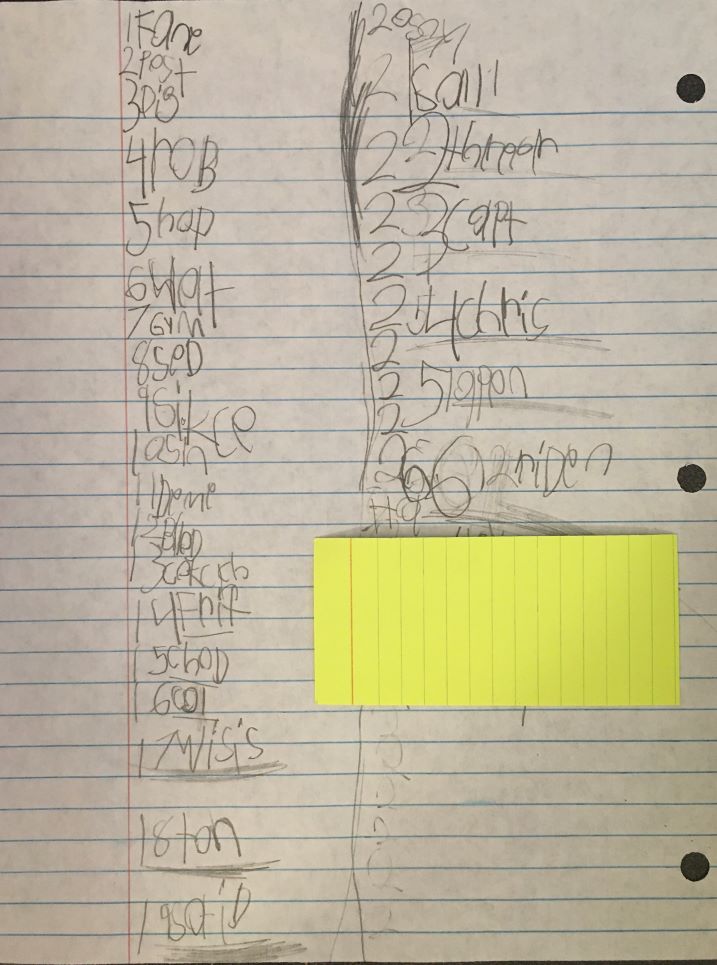

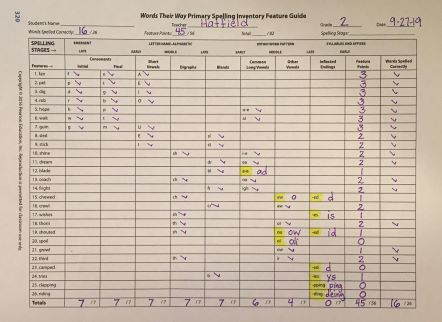

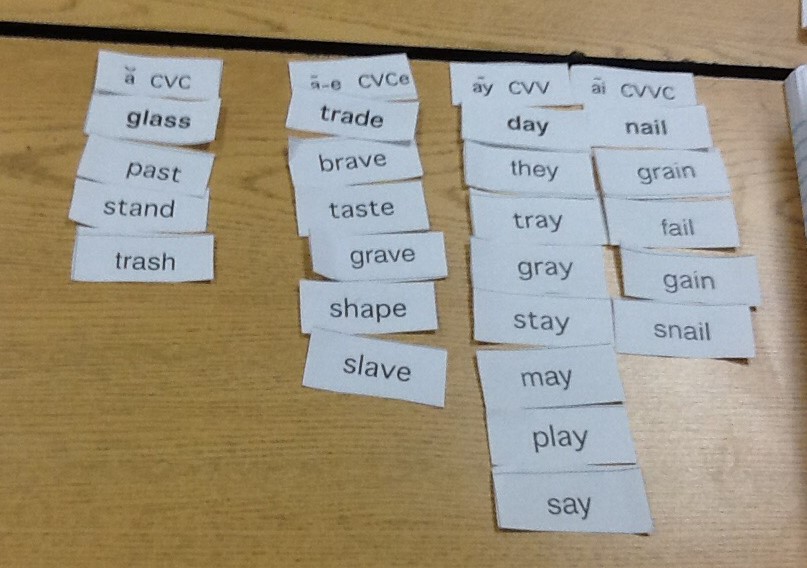

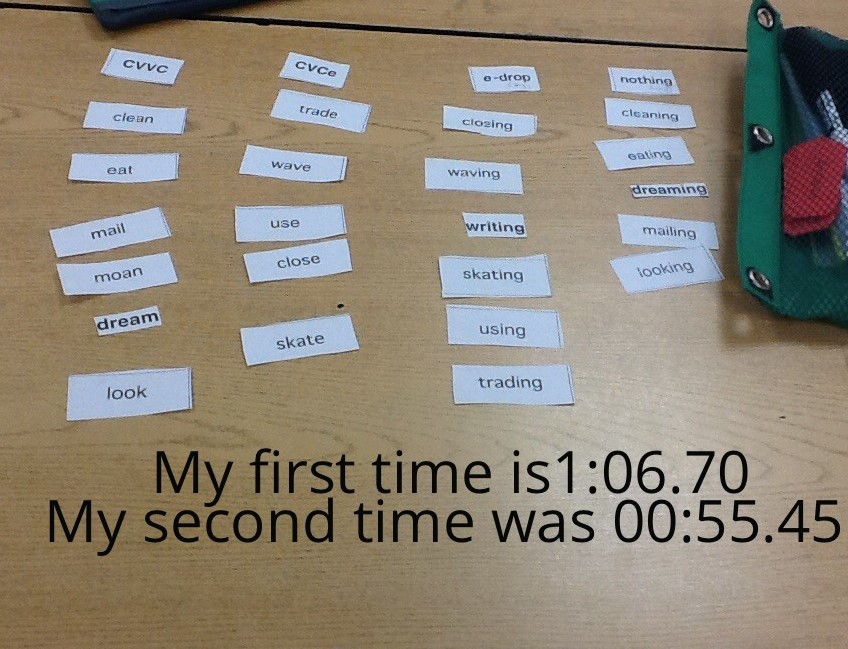

Teachers

should make spelling instruction a priority because spelling specialists

believe that student exposure and exploration through writing is not enough

(p.334). Since students in the same

classroom are on various levels, spelling instruction should be individualized.

Teachers and students work together to select words that need to be practiced

each week using the students’ recent writing as a guide. According to Shane

Templeton and Darryl Morris (1999), the selected words should be “known as

sight words” (p.336), should be words that students will use frequently, and at

the primary level, the words should follow a consistent spelling pattern. Since the class doesn’t have one spelling

list for all students, the teacher is not able to administer weekly pre-tests

and post-tests. Students will work cooperatively in pairs to complete the tests

as well as studying together daily throughout the week.

When considering

grammar instruction, teachers should be aware that research shows teaching the

rules of grammar in isolation through drilling practices is not effective

because students don’t make the connection between the worksheet practice

activities and their own writing. (Hillocks, 1986) Students should be taught

grammar through the use of authentic writing—mentor texts, teacher modeling,

and students’ own writing pieces. Teachers should also help students understand

that the structure of written language, just like spoken language, varies

depending on setting, purpose, and audience. “For example, the grammatical

structures used in writing a letter for publication in a newspaper are

different from those used to write a letter to a grandmother.” (p.339)

Punctuation and capitalization instruction should also be implemented through

using mentor texts and students’ writing pieces. Teachers can instruct students

editing skills through the use of checklists and modeling editing marks.

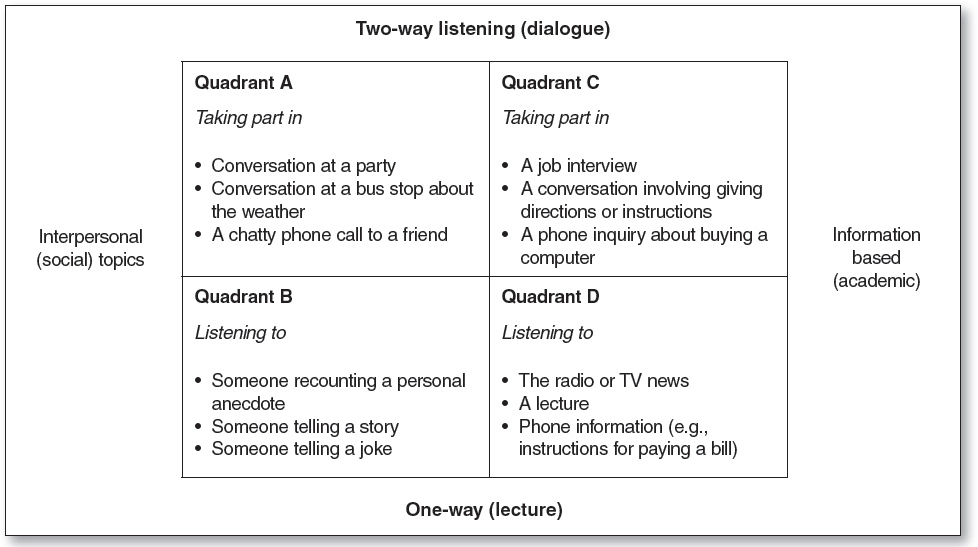

To support

EL learners in the area of mechanical skills, teachers must provide a multitude

of opportunities for structured conversations with their native speaking peers.

Development of oral language in context will increase their understanding and

use of the structures of grammar. Teacher modeling is also vital for ELLs in

addition to giving students daily opportunities to write about topics of

interest to them, experiences that are “in their wheelhouse” so to speak.

Detailed feedback about their writing will assist ELLs with grasping the

correct usage in English for grammar, punctuation and capitalization.

Reference:

Christie,

Enz, Vukelich, & Roskos (2014). Teaching

Language and Literacy Preschool Through the Elementary Grades (5th

ed.).